It starts with an apple. Not quite perfect, maybe sporting a blemish, or perhaps slightly misshapen. Nothing grotesque, nothing inedible. Just not quite the pristine fruit you expect to see in magazines, grocery store displays, or on Instagram. And yet, that apple, in its very imperfection, becomes the seed of something radical. It prompts a question, ‘Why do we reject the almost-right when almost-right can still nourish, still delight, still matter?’

Misfits Market was born from that question. Founded in 2018 by Abhi Ramesh, this company has pursued a simple, almost poetic mission to rescue misfit or surplus produce, fruits, and vegetables that conventional retail would otherwise set aside, making them accessible and delivering good food at a lower cost to households. It’s part business, part moral experiment, part environmental protest. As we follow its trajectory, what emerges is a story of imperfection, value, system-change, and what this means for how we think about food, waste, and the people who shop for both.

Table of Contents

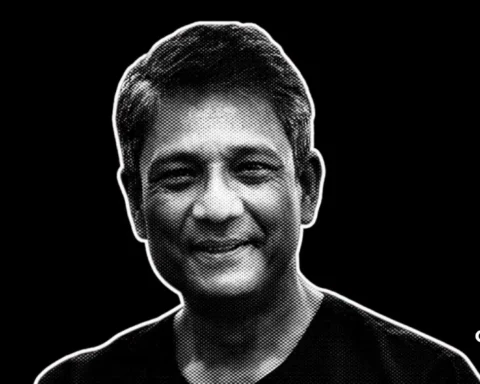

Abhi Ramesh: Why One Founder Decided to Make Ugly Beautiful

Abhi Ramesh grew up thinking about many things —markets, finance, waste, access, etc. His early ventures, StoreTok, education tech, and investment roles, never quite satisfied the urge to build something that married impact and scale. Then came the moment among the apple trees. He saw bins full of apples that were perfectly edible but didn’t meet the arbitrary standards of size and colour. He learned that vast quantities of produce get tossed or composted not because they are bad, but because somebody decided they look “wrong.”

That frustrated Ramesh. It made him want to dismantle that decision, to reimagine what quality means, and whether we need luxury in appearance to connote worth. So in June 2018, Misfits Market was born. It was born to subvert– to take what is surplus, what others discard for cosmetic reasons, and find homes for it in kitchens and on tables.

Ramesh’s ambition was not just to sell odd-shaped produce, but to build infrastructure- better sourcing, better distribution, better access. He didn’t want it to be a niche of the ethically minded but for it to be mainstream enough that saving food becomes a habit, not a specialty. He understood that only scale creates cultural change, and that culture, not charity, was the terrain on which this battle had to be fought.

The $2 Billion Business of Rescuing the Ugly: What’s Underneath Misfits Market’s Numbers and Strategy

Misfits’ growth has been impressive. From a small subscription box idea to a company now valued at around $2 billion, it has shown that there is demand for ugly produce, not merely among morally conscious consumers, but among households seeking good food at less cost.

Its business model hinges on three pillars:

- Supply: Misfits sources from farmers who otherwise lose revenue. These are small‐ and medium‐scale farms whose produce is rejected for size, shape, or color. What might end up wasted, Misfits moves into fulfillment and onto customer boxes.

- Efficiency / logistics: Since produce is perishable, speed, cold chain, and transportation cost become crucial. Misfits has to aggregate surplus produce, route it quickly, maintain freshness, and deliver at scale. They also channel some produce toward food banks when feasible, though transportation costs and infrastructure remain constraints.

- Customer value + narrative: Part of what makes the business compelling is the story: “you’re helping reduce waste”, “you’re getting quality at lower cost”, “your standards are helping farms stay in business”. The narrative is as important as the fruit. It transforms an ordinary grocery transaction into something more ethical, more engaged.

Yet growth introduces contradictions. Margins are tight when production is unpredictable. Customer expectations around appearance still persist. Logistics, especially to remote zones, increase costs sharply. Scale demands capital. Competition from imperfect foods and from traditional retailers adopting similar language complicates the landscape. Scaling without mission drift is not an easy balancing act.

Rethinking Food Systems, Waste, and Our Notions of Beauty in Harvests

There is a deeper cultural critique embedded in Misfits’ work. When we reject an apple for being slightly discolored or oddly shaped, we are rejecting not just that fruit but a chance to shift our standards. We’re saying appearance trumps taste, shape trumps substance, and perfection trumps honesty.

Misfits exposes the waste in that system, both literal waste in fields and farms, and moral waste in how we define “good” produce. By doing this, it nudges the food system and forces farms to think differently about what they can sell. It pushes retailers to recognize that “imperfection” doesn’t equal “worthlessness”, challenges consumers to trust their senses beyond sight, and demands infrastructure in transportation, cold storage, and logistics that supports the ugly and the surplus just as much as the flawless and the fashionable.

Environmental stakes are high. Rescuing food reduces carbon emissions (less food rotting and releasing methane), reduces the burden on landfills, and optimizes land already cultivated. Social stakes matter too! Lowering the cost of good food for more households means better nutritional access. And in markets, it forces innovation, disrupting supply chains to create new norms. In this sense, the company is more than a grocer; it is a cultural agent.

A Few Small Questions That Matter for What Comes Next

- How much of the “ugly produce” rescued by Misfits ends up unable to be used for food (due to spoilage, logistics)? That leakage affects both cost and environmental gains.

- To what extent does the growth of Misfits push large retailers to change their own sourcing and aesthetic standards?

- Can the cost savings to consumers remain stable as the company scales, or will rising complexity and transport costs raise prices?

- What trade‐offs might emerge between reducing waste and minimizing packaging, transport emissions, and other unseen costs?

- How does consumer perception, taste, appearance, and freshness get managed so that people don’t reject produce simply because it looks different?

These questions are not footnotes. They determine whether Misfits can remain both profitable and transformative, or whether it will simply become another grocery service with a sustainability narrative attached.

Why This Kind of Imperfect Model Might Be a Template for Other Industries

Agriculture and food are vivid because waste is visible, fresh produce spoils, and beauty standards are deeply ingrained. But think of sectors like fashion, where overproduction, cosmetic perfection, and waste of usable material are rampant, or in manufacturing, where parts that are “good enough” are discarded in favour of aesthetic uniformity, or even in digital content, where high-resolution perfection demands costly bandwidth.

The same underlying logic applies: what we deem perfect is often a luxury that produces waste, and what we reject may still serve a deeply important purpose. Abhi Ramesh suggests a template- find what we discard, reframe its value, build supply‐chain infrastructure to capture it, shape customer expectations, align environmental, financial, and moral incentives.

It’s not easy. In fact, it’s exhausting work because it asks for cultural patience and operational brilliance at the same time. Yet the possibility it opens is real. For a world confronting climate change, resource scarcity, and widening inequality, such models hint at a different promise: that our future may not need to be flawless to be better.

FAQs

Who is the CEO of Misfits Market?

Abhi Ramesh. Not just a founder, but someone who saw in discarded fruits a question worth answering, a question that became a mission, a company, and a subtle cultural challenge to how we value food.

Is Misfits Market actually worth it?

Worth it depends on what you measure. If it is taste, nourishment, and ethical consumption, then yes. If it is perfection in appearance, perhaps not. Misfits Market asks its customers to reconsider what “worth” truly means.

Is Misfits a good brand?

Goodness here is determined not by glossy packaging, but by impact. A brand that turns what is rejected into opportunity, that nudges culture and systems to think differently, can be considered good in a way that goes beyond conventional metrics.

Where is Abhi Ramesh from?

He comes from the world of observation and inquiry, first in ventures across tech and finance, then in orchards and farm fields, where he noticed what others overlooked. Geography matters less than the mind and the questions it asks. But still, he was born in India and lives in Atlanta.

Is Misfits Market cheap?

Cheap is relative. It is certainly more accessible than traditional premium produce.