The issue of the caste system is nothing new, but it has also not become cliched or oblivious. It is very much a problem of the past, present and future. But some people tend to think otherwise- they tend to associate reservation with the lack of job opportunities. They think that the caste system is a matter of remote past, and it is now been used as a pawn to gain privilege in the job market.

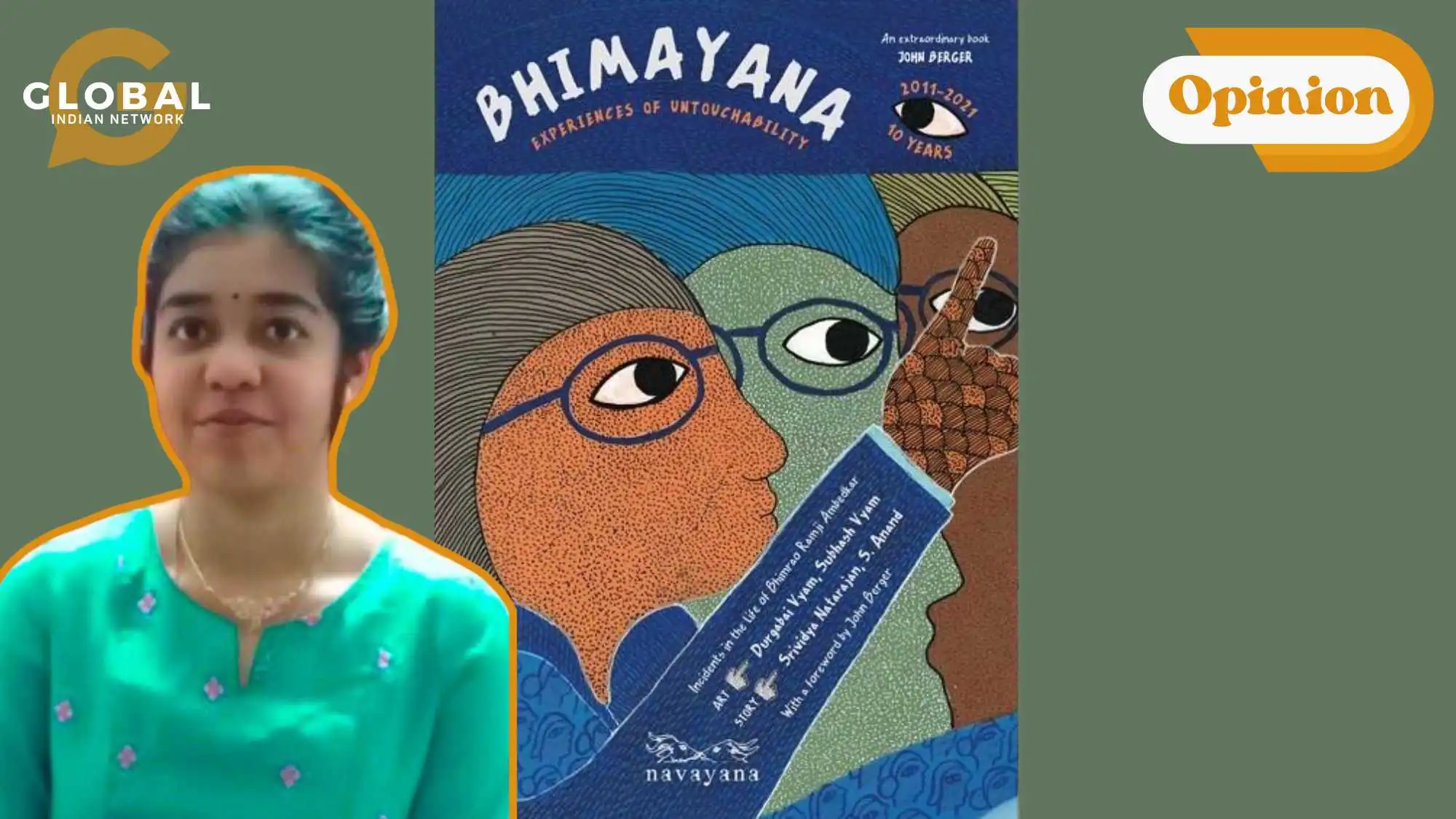

In an attempt, to break this illusion, rethinking the caste issue was important. So, Bhimayana was published by Navyana publishers and this graphic novel was created by the joint effort of artists- Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam and writers – Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand in 2011.

Pattern of Bhimayana

Artform

Bhimayana is unique in its content and form as, unlike the classic comic pattern of gutters and panels, it chooses the digna as a form of khulla pattern, which is a Gond form of art. The illustrators, Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam said that they do not want to force their characters into boxes, rather they would prefer to give space for all their characters to breathe.

The use of the Pardhan or Gond art form is also symbolic in terms of rethinking the caste issue. It is significant as the tribal art form creates a subversion to a European-constructed structure or sophisticated art form. Moreover, as Gond’s art shows reverence to Mother Nature, it is perhaps indicative that human beings are equal in the eyes of Nature and the caste system creates artificial barriers to divide man.

Title

Even, the title of Bhimayana has been chosen carefully to counterpoint Ramayana, the title of the biographical tale of the Hindu mythological leader, Rama. Bhimayana is also a biographical tale about the Dalit leader, Bhim Rao Ambedkar but it is different, as his story gets weaved with the story of many untouchables. In P.K. Nair’s words, it is “ the story of a collective.”

Plot

Bhimayana at its very outset, is divided into four chapters– ‘Water’, ‘Shelter’, ‘Travel’ and ‘The Art of Bhimayana’. It is apparent from the title of the chapters, at least the first two, that the graphic novel deals with the encroachment of the necessities of life. However, the text gets introduced with the debate between the two sutradhars (narrators) regarding the pertinence of reservation.

Bhimayana knits the scarps and bits of the life of Ambedkar, mainly the ostracization faced by him with the contemporary newspaper accounts of Dalits being mutilated, raped, strangled and killed. The plot line starts with Bhim’s childhood where the first site of discrimination he faced was in school, the place which ideally should be the forum of equality.

Water

School Life of Ambedkar

Delving into the chapter, ‘Water’, it becomes suggestive of the theme regarding the primary life force of sustenance. In the school in Satara, where Young Bhim used to study, the teacher felt irritated whenever he asked for water. But whenever the bell rang, and he used to go to the peon to fetch drinking water, he turned a blind eye.

Even after patiently waiting, the peon refused to fetch water, giving the excuse, that he could not let Bhim touch the tap, lest it be polluted. The peon is even reluctant to fill the pitcher to pour water for him. The readers will be surprised to know that the teacher gave a solution, that if Bhim cuts his hair, he would feel less thirsty, being oblivious to the fact that barbers did not even touch the hair of Mahars (untouchables).

It is indeed crucial to note that the status of untouchables is relegated below the animals, and they are deprived of the basic source of life, water. An ironic situation is put forth, when Ambedkar’s father built a new tank in Goregaon for the government to help the people affected by famine, whereas his son is denied access to water in school.

Travel to Goregaon

Another incident is illustrated, when the ten-year-old Bhim along with his brothers, travelled all the way long to visit his father in Goregaon being deprived of drinking water. Being born in the family of Mahars, the cart man who took them from Masur to Goregaon, told them that they could only have water from the cattle pool, before reaching their father’s home. These incidents forced him to rethink the caste issue and to do something for the Dalit community.

Shelter

The oppression even continues, when Ambedkar has returned as a well-educated man from the University of Columbia of America. Being away from India, he nearly forgot about this social apartheid. As the readers are plunged into the next section ‘Shelter’, it becomes apparent that even education does not serve as the gateway to elevation or equal treatment.

When Ambedkar returned from Columbia to the state of Baroda, in Gujarat to work as a probationer in the Accountant General’s office, to repay the debt of the education loan given by Maharaja of Baroda. The readers become shocked as he is unable to manage a shelter for himself. He pleaded with his friends and even feigned a Parsi name in the register of the Parsi Inn.

After four days of staying in the inn, too much of his surprise, the Parsis who do not have any segregationist policies, oust him, having found him to be untouchable. Hopelessly, squandering for shelter, he decided to board the train back to Bombay and take a temporary shelter in the Kamathi Baug, which is a public garden.

Travel

The hypocrisy gets further intensified in the chapter ‘Travel’. It becomes apparent that people of different religions like Christians, Parsis, and Muslims also look down upon untouchables of the Hindu religion. Even, a person belonging to the lower class gives a scornful eye to the Mahars. This part ends when the narrator at least starts rethinking the caste issue and the acceptance of the prevailing caste-based inequality.

If one places the narrative syllogistically, then in the ending towards the part ‘Water’, there is a mention of Ambedkar undertaking Mahad Satyagraha. After having completed his higher studies at foreign universities, he started a massive Satyagraha in Mahad in 1927, asserting a move that the Dalits should be allowed to access water from the Chavadar public tank. Though it seemed to be successful at first, the Brahmins did not stop their nuisance. They started to pollute the water and dump garbage in the pond, turning it into a sewer.

The point is at least the movement boosted the confidence of the Dalits and shook the hedonistic Brahmans, giving them a lesson that all things cannot happen according to their whims.

Conclusion

Bhimayana being a graphic novel, involves both visual medium as well as textual matter, which indeed helps the audience to grasp the matter. When rethinking the caste issue is the matter which is a serious issue of societal importance, then it is vital to render it in a feasible medium

With the ecology of Pardhan Gond’s art form by using animals, birds trees and different colour hues, the graphic novel indeed has reached a different edge. Bhimayana has tried to bring the issue of caste closer home, unlike the misconceptions that clouded the minds of many, through a popular form of art as well as literature.

But the question remains whether Bhimyana is successful in changing the conception of people. Will people start rethinking the caste issue in a new light? Will the problems regarding reservation change? Will people stop grudging and equating the reservation with inequality?

Will people stop discriminating against the Dalits? What do you think about the same? Let us know what you feel in the comments section below. If you have an opinion to share, feel free to reach out to us at larra@globalindiannetwork.com.